George McJunkin: The African American Cowboy Who Made A Monumental Impact On American History

The Wild West cowboys Billy the Kid and Buffalo Bill are household names. George McJunkin, not so much. That’s a shame because McJunkin made a significant contribution to US history.

In fact, his singular discovery radically changed our understanding of how the North American continent developed in the first place! Something like that belongs in the history books, so why was he forgotten for over 100 years? Let’s find out.

Self-Taught Cowboy

If you were strolling around northern New Mexico in the latter part of the 19th century or early part of the 20th, you may have come upon George McJunkin.

Source: Texas State Historical Association/Wikimedia Commons

He was an African American cowboy born to enslaved parents in 1856. As he grew up, he took work as a cowboy, taught himself to read, speak Spanish, play the guitar, and be an amateur archeologist. The natural world fascinated him, so he collected plenty of artifacts during his travels.

Foreman at Crowfoot Ranch

McJunkin got work as a buffalo hunter. He roamed the Great Plains – a vast area taking up much of the central United States, from the Rocky Mountains in the west to the Mississippi River in the east – to track and hunt these great beasts.

Source: Roman Garcia Mora/Stocktrek Images/Getty Images

He moved around a lot, mixing in his buffalo hunting with farm work. Eventually, however, he settled down in Folsom, New Mexico for a while. On the nearby Crowfoot Ranch, he got himself a job as a foreman.

Monumental Discovery

In late August 1908, an enormous flood swept through Folsom, New Mexico. It claimed the lives of 18 people. Shortly thereafter, McJunkin went to Crowfoot Ranch to get a better handle on how much damage was done.

Source: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration/Wikimedia Commons

As you might have guessed, Crowfoot wasn’t looking too good. However, in the midst of surveying the wreckage and repairing a broken fence, McJunkin found something that stopped him in his tracks. Like many monumental discoveries, McJunkin had no idea just how monumental it would turn out to be.

No Credit

What’s even more frustrating – and tragic – is that McJunkin’s discovery on Crowfoot Ranch was never adequately recognized. Although he had an inkling that what he found was important – which is why he showed so many people during his life – the public just wasn’t interested.

Source: Tig Productions

McJunkin went to the grave without knowing the full impact of what he found. About five years after his death, however, the archeology world gradually changed its tone. They took note of McJunkin’s discovery, but he wasn’t around to see the praise.

McJunkin’s Early Life

Although it took nearly a century, archeologists, journalists, and the general public are finally taking a keener interest in the life of this remarkable cowboy. It’s about time.

Source: Kurz & Allison/Wikimedia Commons

It’s a life that began in 1856 … if you want to believe his tombstone. However, quite a few other commentators say that George McJunkin’s life began in 1851. Although dates are disputed, everyone agrees he was born in Texas before the Civil War. After the bloody Civil War came to an end, McJunkin decided to head over to New Mexico.

Handy Man

McJunkin’s early life was closely entwined with that of horses. They were everywhere, so it’s no surprise that George became a gifted horse rider. In addition to that, George’s dad was a blacksmith, so he knew quite a bit about working with metals.

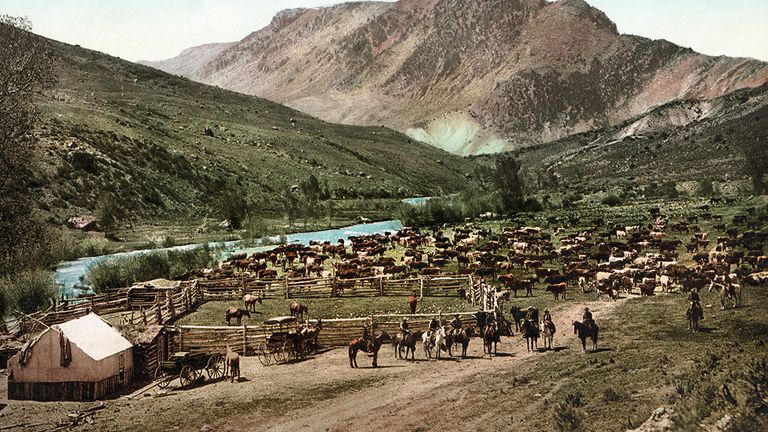

Source: William Henry Jackson; Detroit Photographic Co./Wikimedia Commons

Finally, he was very skilled with ropes. Taken all together, the horseriding, metal work, and rope skills meant that George had all the skills required to work on a ranch. So that’s exactly what he did over in New Mexico.

Cowboy Scholar

Shortly after arriving in New Mexico, McJunkin started working on ranches and quickly rose up the ranks. He decided to be a cowboy, so he set to work breaking in horses and herding cattle.

Source: Warner Bros.

He became incredibly skilled at what he did, and pretty soon all the local ranch hands were well aware that he was one of the most talented cowboys around. It didn’t stop there, however. McJunkin also had an insatiable curiosity – especially when it came to learning about science.

Learning to Read

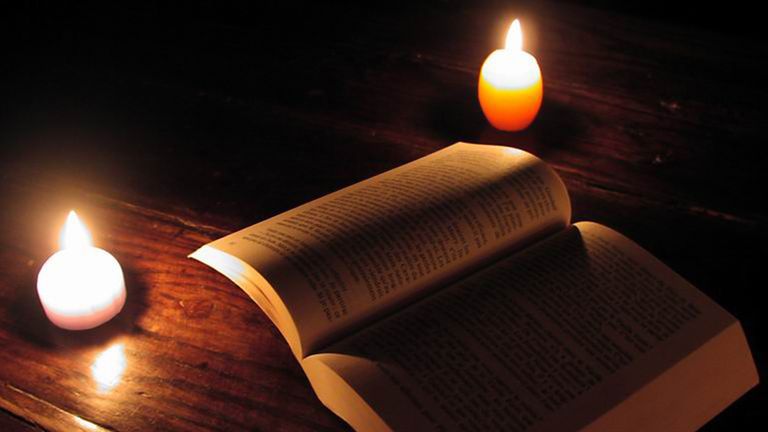

The life of a cowboy is difficult. The workdays are long, rough, and full of physical exertion and bad weather. While excelling at that, McJunkin also managed to set aside enough time to learn how to read.

Source: Romain Vallet/Flickr|CC BY 2.0

His cowboy partners taught him to identify the letters, understand the punctuation marks, and comprehend entire sentences, paragraphs, chapters, and books. McJunkin loved it. As if the work of being a cowboy and learning to read wasn’t enough, he also practiced speaking Spanish and played the fiddle.

Becoming the Manager

Day after day and week after week, McJunkin consistently showed that he was reliable, capable, and responsible. The ranch owners, taking notice of his skills and character, decided to promote him to the estate manager. Unsurprisingly, McJunkin accepted their offer.

Source: The Weinstein Company

The ranch was known as Crowfoot Ranch. It was a remote place just outside the small little town of Folsom in northeastern New Mexico. Here was where McJunkin would eventually make a world-shattering discovery. That discovery would later be named after the town of Folsom.

Disastrous Flood

On August 27th of 1908, something terrible happened. The sky looked ominous as the dark clouds turned day into night. Then, the rain began to fall. It pelted down with a tsunami-like intensity that scared the townsfolk and ruined the land.

Source: Jason Weingart/Future Publishing via Getty Images

Folsom was not looking good. Water levels surged all throughout the small town, completely overwhelming it. The Folsom flood of 1908 was an absolute disaster. Not only was it the most destructive flood in living memory, but it was also the most destructive flood since records began.

A Terrible Flood

In the local newspapers of the time, journalists painted dire pictures of the carnage of the flood. It was like the whole Pacific Ocean came in to cover the town. Water filled all the streets, making them into tiny rivers.

Source: john finney photography/Getty Images

Furthermore, all the houses and bakeries and saloons were completely destroyed by the force of the waters. Residents scampered to their roofs, the highest place they could find, to find safety. Unfortunately, not everyone was so lucky – at least 18 people died that day.

The Damage Done

Shortly after the catastrophic flood subsided, and the worst of the damage was done, George McJunkin left his home and rode on out to Crowfoot Ranch to see the damage. By his side was his buddy Bill.

Source: The Weinstein Company

They rode together to get the best picture they could of how the flood affected the entire ranch. It wasn’t pretty. However, somewhere along the way, George’s eye noticed something odd. He looked again to find a newly created waterway that must have formed from the flood.

A Strange Discovery

Curiosity got the better of him, so McJunkin rode on down to get an up close and personal look at the new waterway. Although McJunkin didn’t know it at the time, that decision would prove to have a huge impact on his life.

Source: Jack Dykinga/Wikimedia Commons

Within minutes of investigating the stream, he found something far more interesting than the stream: a pile of bones. Not just any pile, these bones were massive – far larger than the bones of any buffalo he knew.

Bringing Back Bones

The discovery of bones stopped McJunkin in his tracks. As a cowboy and a budding amateur scientist, he knew that these bones were unlike anything he’d seen before. The size alone suggested that they didn’t belong to any creature currently roaming the earth.

Source: The Weinstein Company

Instead, they must have belonged to something long dead – an extinct species not seen for who knows how long. Although he didn’t have the specifics to back him up, he had a hunch that this was a remarkable discovery, so he brought back some of the bones.

Trying to Spread the Word

So, in that late August day of 1908, George McJunkin rode back home with the mysterious bones of a creature that would eventually change American archeology forever. Unfortunately, it would take a long time to do so.

Source: The Weinstein Company

McJunkin tried to bring the bones to the attention of archeologists and others with a serious interest in the past. However, all his efforts were in vain. For some reason, no one wanted to pay attention to the huge discovery being offered to them. Regardless, George kept on trying for 14 long years.

All in Vain

Whenever he had some spare time – which, considering he was the head of a ranch in a rugged business, wasn’t a lot – George would write letters and send them off to experts in the field. He also showed the bones to some of the same experts.

Source: The Weinstein Company

Nothing. None of the experts took enough interest in the bones to come to investigate them or the site further. Why? It’s hard to tell, but it is so. In 1922, nearly a decade and a half after his discovery, George McJunkin passed away.

Finally, the Word Spreads

After 14 long years of sending off letters and pleading with experts to come to look at the giant bison bones, George died. A few months later, one of those experts finally decided to take him up on the offer and visited the site.

Source: The Weinstein Company

His name was Carl Schwacheim, and he didn’t come alone. Instead, he brought a proper team along to investigate in-depth. Shortly after they arrived, they knew that George was right: this was the home of giant bison bones.

An Expert Visits

Like the process of bones fossilizing over thousands of years, progress in archeology moves at a slow pace. So, although Schwacheim and his team confirmed McJunkin’s hunch, nothing much happened for many years after that. The bones stayed still.

Source: The Weinstein Company

However, in 1926, there was a glimmer of hope. One of Schwacheim’s crew members managed to persuade one of the experts at the Colorado Museum of Natural History to come down to the site for a visit. His name was J. D. Figgins, and he instantly knew the site was important.

A Hunch Confirmed

After his instant recognition of how important the site was, J.D. Figgins organized a proper archeological dig. With the help of his colleague Harold Cook and others, the team reached early success with a significant discovery.

Source: Arthur Lakes/Wikimedia Commons

In short, they confirmed what McJunkin thought ever since he discovered the bones in 1908: the bones belonged to a species of extinct bison. Furthermore, the crew found that the extinct bison bones weren’t the only bones there. Instead, the remains of 30 other animals were nearby as well!

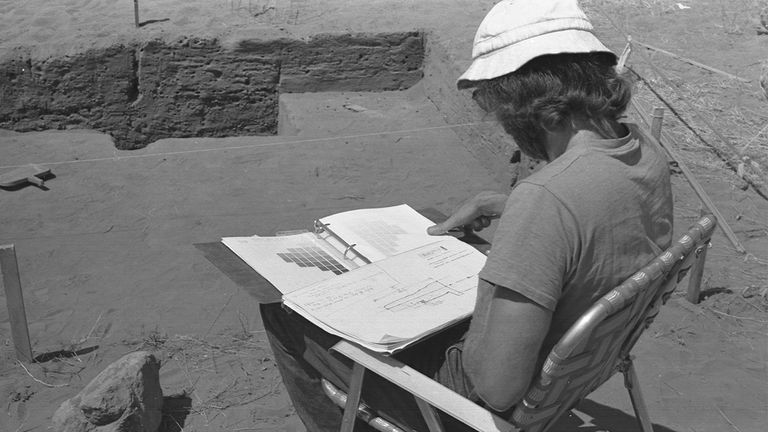

Excavating Away

As you might imagine, Figgins’ interest in the site only deepened – he knew it was something special. So, the crew continued to painstakingly excavate beneath the hot New Mexico sun. They were absolutely certain they would find the remains of other animals buried for hundreds or thousands of years.

Source: James St. John/Flickr|CC BY 2.0

That may be true. But along the way, Figgins’ crew would discover something even more fascinating about the site: extinct animal bones weren’t the only thing buried there. Something closer to home was as well.

Other Interests Emerge

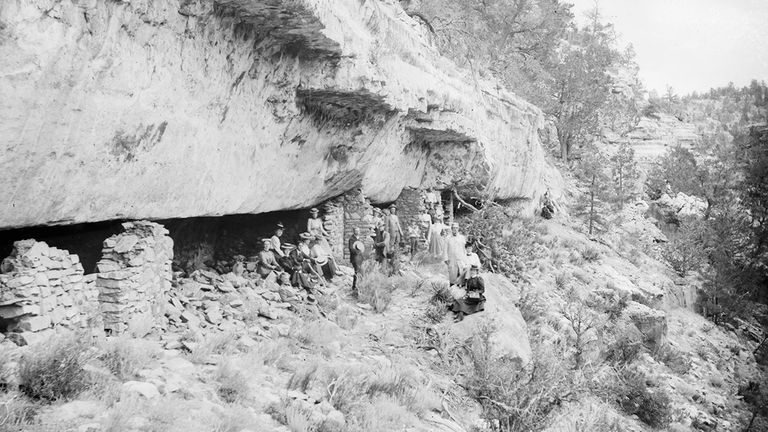

Alongside his interest in extinct animals, Figgins was also interested in ancient people. In particular, any ancient people that might have lived in North America. How far back did they go? Trying to answer that question was difficult considering the lack of physical evidence.

Source: C. C. Pierce/Wikimedia Commons

So, while he spent his days excavating and detailing the finds, Figgins also had the idea of ancient North Americans in his mind. However, he never thought the two interests would collide in one convenient place: McJunkin’s site.

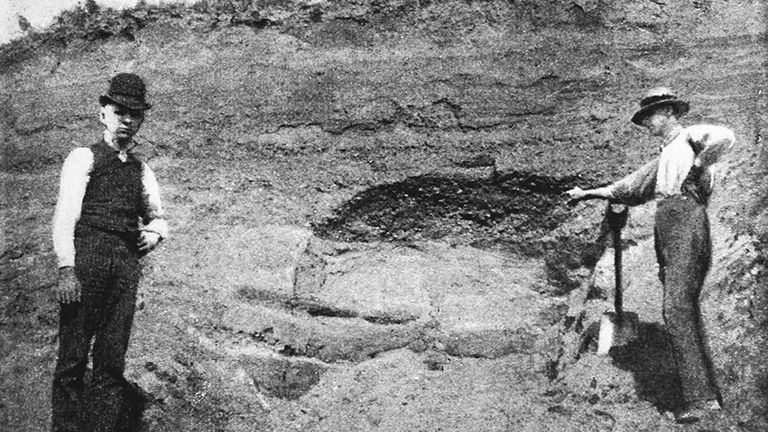

Discovering an Artifact

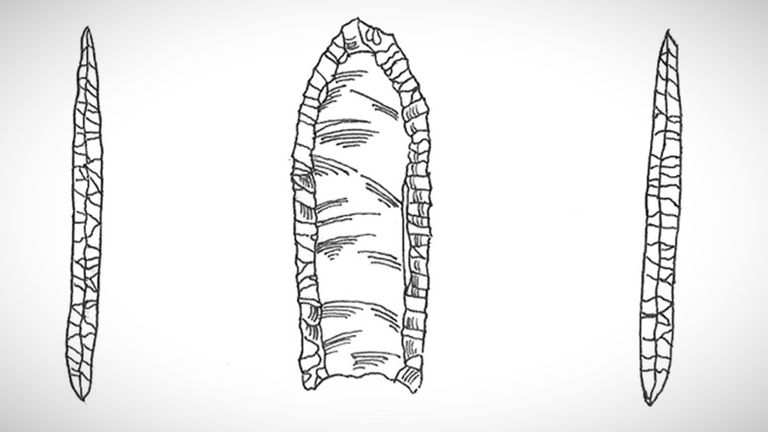

While excavating in the hot New Mexico summer of 1926, Figgins’ team of archeologists unearthed something a bit odd. One crew member was shoveling away dirt when he found something that clearly wasn’t a bison bone. Neither was it the bones of any other animal.

Source: Jerónimo Roure Pérez/Wikimedia Commons|CC BY-SA 4.0

Instead, it was an artifact. As the crew members examined it closer, it became clear that the artifact was the head of a spear. The entire thing was made of stone and buried in the ground long ago.

Finding More

Although they had a vague idea of what it was and what it was made of, they had no idea who made it, how long ago it was made, and what it all meant. The questions piled up much faster than the answers.

Source: SeriouslySerious/Wikimedia Commons|CC BY-SA 4.0

So, the following year, they went back to the site for a second excavation. Sure enough, they found another spearhead made of stone. They reached out to other archeologists to get a better idea of what was going on there.

Very Ancient People

Word of the exciting new find spread throughout the archeological community. Soon, a consensus emerged: the stone spearheads belong to a group of ancient people. Furthermore, the fact that the spearheads were right next to the bones of an extinct bison meant something even more profound.

Source: James St. John/Flickr|CC BY 2.0

Namely, the ancient people were very ancient – far older than any civilizations that people studied at the time. Soon a number emerged to give a precise date to how ancient they were: 11,000 years old!

Some Important Context

Nowadays, hearing that ancient people lived in New Mexico 11,000 years ago is interesting, but not necessarily earth-shattering. That’s why it helps to understand this fact within the context of what people thought back in the 1920s.

Source: wellcomecollection.org/Wikimedia Commons|CC BY 4.0

Back in the first few decades of the 20th century, the most respected archeologists and historians believed that people had been on the North American continent for 3,000 years or so. Finding out that it was actually four times longer must have been mind-blowing.

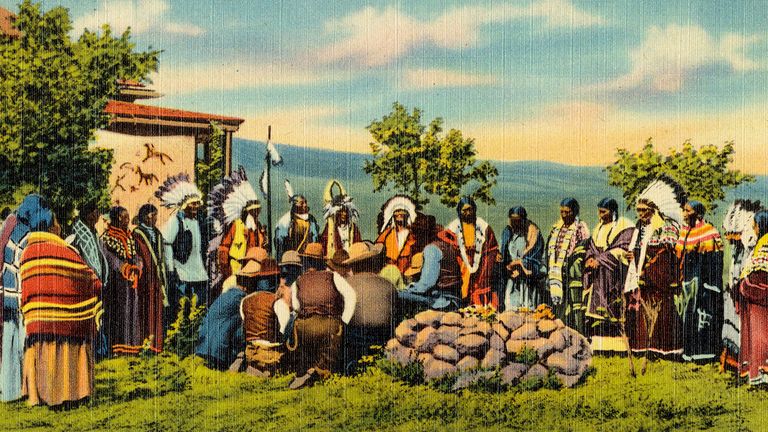

Native Americans Already Knew

Who would have thought that the site McJunkin found when surveying Crowfoot Ranch after the devastating flood of 1908 would eventually – a few years after his death – lead archeologists to radically reconsider how long humans had been in North America. It’s amazing.

Source: Jewel Huwe Pub., Lemmon, S. Dak./Wikimedia Commons

That being said, many Native Americans didn’t find it as mind-blowing as the archeologists. That’s because they already knew their history went back a lot longer than prestigious archeologists assumed. The Folsom site excavations simply vindicated their knowledge.

Rewriting History

At the end of the day, it took a stone arrowhead dug up at a site near Folsom, New Mexico to rewrite the history of the Americas. Furthermore, it took George McJunkin’s unwavering attempts to spread the word about the site he discovered.

Source: Bureau of Land Management/Flickr|CC BY 2.0

Although it was ultimately in vain during his lifetime, in death, his site was vindicated many times over. Without McJunkin’s discovery, archeologists would have taken a lot longer to understand just how ancient the history of the Americas really is.

Erased From History

The question then becomes, why was George McJunkin’s role erased from this archeological story of the century? To be fair, McJunkin wasn’t a trained scientist and he wasn’t specifically interested in tracing back the history of the Americas.

Source: Capture The Uncapturable/Flickr|CC BY 2.0

And yet, despite his lack of formal qualifications and academic interest, he knew in his gut and through his reading that the site had to be significant. That’s why he tried so hard to spread the word. So why isn’t the name “George McJunkin” better known?

White Supremacy

When articles about this amazing site started to trickle out into the archeological world, one name, in particular, was absent from all of them: George McJunkin. Why was that the case? Shouldn’t he have been given credit for the discovery?

Source: John Atherton/Flickr|CC BY-SA 2.0

Examining some of their political affiliations yields an uncomfortable answer to the reason for McJunkin’s absence. J.D. Figgins, who headed the excavation, was a member of the Ku Klux Klan. As part of that notorious white supremacy organization, Figgins was uncomfortable giving a Black man any credit.

McJunkin Gets Credit

Although Figgins never gave McJunkin any credit, other archeologists did as the years went by. According to a January 2022 article in Sapiens, a well-respected archeology magazine, McJunkin’s name shows up in the historical record in 1946.

Source: Xerxes2004/Wikimedia Commons|CC BY-SA 4.0

It was at that time that the author Frank C. Hibben published a book titled The Lost Americans. In it, he claimed that George McJunkin found the bison bones. However, he also claimed that McJunkin found the spearheads as well, and did it all in 1925.

Setting the Story Straight

Since McJunkin died in 1922 and didn’t know about the spearheads at the time of his death, those other two claims were wrong. Regardless, they sparked interest in learning more about McJunkin’s story. George Agogino, an archeologist writing for New Mexico Magazine, set out on a quest to find the truth.

Source: via Wikimedia Commons|CC BY-SA 4.0

Agogino wanted to know McJunkin’s exact role in the Folsom site discoveries. So, he set about reading all the material he could and mixed that with oral stories passed from person to person.

Redefining McJunkin’s Role

After much diligent research, Agogino was able to confirm that George McJunkin did in fact find the ancient bison bones on Crowfoot Ranch. He was also able to confirm that he didn’t know about the spearheads.

Source: David Monniaux/Wikimedia Commons|CC BY-SA 3.0

He confirmed it after looking through all the available archives. Later on, Agogino wrote that there wasn’t “a single sentence suggesting that McJunkin found, or even considered, the hand of man in the destruction of the bison.” Although that may seem like it diminishes McJunkin’s role, it respects him by being accurate.

A New Chapter

Not knowing that humans were also with the ancient bison didn’t reduce Agogino’s praise for McJunkin one bit. Instead, he lavished praise on him by saying that McJunkin’s discovery was “the start of a new and thrilling chapter.”

Source: Internet Archive Book Images/Flickr

That chapter was in a book that told the story of American prehistory, something that archeologists had precious little knowledge of before the Folsom site was found. Eventually, it grew into a story of how Paleoindians crossed the Bering Strait over 12,000 years ago.

Muddled Origins

McJunkin’s pivotal role in this larger story was muddled in the early years. First, the fact that the head excavator was part of the KKK. Second, by the passage of nearly 38 years from the time of McJunkin’s initial discovery to accurately giving him credit for it in print.

Source: Popular science monthly/Wikimedia Commons

This muddle origin tale contributed to McJunkin’s erasure from history. If only the first archeological crew wrote honestly about how they came to find the Folsom site, all this unpleasantness would have been avoided.

Proper Credit

For being the kind of man who followed his curiosity, made a monumental discovery and tried (in vain) to spread the word, George McJunkin deserves his place in the history books.

Source: $1LENCE D00600D/Wikimedia Commons|CC BY-SA 3.0

And, although it took a very long time, that finally came to be. In 2019, almost a century after his death, the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum added George McJunkin to its Hall of Great Westerners. He’s in great company, remembered alongside other cattlemen, ranch managers, and historians as well as business leaders and politicians.

Better Late Than Never

Although late is better than never, this is pretty late. George, however, seemed like a man who was accustomed to waiting. After his 1908 discovery, it took nearly 15 years before someone even came to the site.

Source: Tig Productions

Then, it took another 20-some-odd years before his name was attached to the discovery. After that, it would be another 73 years or so before he was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners. As a cowboy, George knew how to be patient – but a century is a bit too long.

Overlooked Achievements

Sadly, the story of George McJunkin is all too common. As a minority – a Black cowboy who was born during slavery and lived his entire life in a highly segregated society – he was used to being passed over, forgotten, or looked down upon.

Source: Björn Allard/Swedish National Heritage Board - Riksantikvarieämbetet/Flickr

The same has happened to many other minorities who made important discoveries throughout history. As Stephan Nash wrote in his Sapiens article, the “credit often goes to the powerful and connected, not to the people who actually do the work.”

Retelling History

Nash continued by writing that, “gender, race, status, and age discrimination often play a role” in what gets remembered. With that in mind, McJunkin’s story and role in history are important to retell because it rewrites some historical wrongs.

Source: wwwuppertal/Flickr|CC BY 2.0

Despite his monumental discovery – a discovery that fundamentally rewrote our understanding of American prehistory –, he was forgotten for many years. Unfortunately, a lot of that “forgetting” had to do with McJunkin’s race – the fact that he was a black man in a white man’s world.

McJunkin’s Spirit Lives

Nash, like McJunkin, is a naturalist and collector who has a deep respect for history. Toward the end of his Sapiens article, he concludes that he thinks “McJunkin would want his own story rewritten so that it can be told accurately.”

Source: James St. John/Flickr|CC BY 2.0

Whether that’s true or not, we can never know because George is long gone. However, his spirit, his “inquiring mind, intrepid spirit, and perseverance” lives on to this day. In between speaking Spanish, playing the fiddle, and managing a ranch, McJunkin transformed archeology forever.